This article was originally published on our Medium blog.

I’ve been traveling all around the world since the new year began — Vietnam, the Philippines, Costa Rica, the United States, Mexico, and the United Kingdom. I’ve seen a lot of places, met a lot of people, and done a whole lot of things in these last seven months.

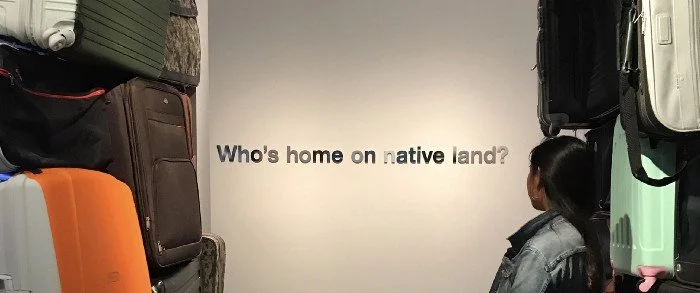

But out of all of the adventures I’ve had, that photo above is the one photo that sticks with me.

It’s not at all spectacular. It’s not even remotely Instagram-worthy. It doesn’t even tell you where I am, really.

And yet it’s the one photo that captures all these complicated feelings of home and living in between that little “hyphen” that I’ve recently become obsessed about — that hyphen bridging East to West, connecting my ancestral home to my adopted one.

This is a photo of me in a newly opened Tim Hortons (the national café of Canada — essentially our equivalent to Starbucks) just a five-minute walk outside of my home in Parañaque, Metro Manila in the Philippines.

So what? Why is this so special or important?

When I traveled to the Philippines this past January, I hadn’t been in my birth country in almost a decade. After the most intense year of my life building not just the pages that were to become Living Hyphen’s inaugural issue but also a community that digs into its roots as people of diasporic communities, this trip felt monumental. It felt like stars aligning, like all the puzzle pieces finally coming together, like a cherry on top of a year of immense discovery.

But when I got there, I was not prepared for the rude awakening that awaited me. I was not prepared for my ideas of home to shatter.

It was on this trip back to the motherland that I realized that what truly made this place a home was the people who I always longed to return to — my family. And it was then that I realized that those people no longer actually live there anymore. Almost all of us have moved abroad.

Never before have I felt so unmoored, so displaced in a place that felt so deeply rooted in me — at least in my memory, in my imagination.

I realized then — definitively — that Canada is home now.

And to find this little pocket of Canada — however capitalistic and kitschy or flimsy a symbol it might be — felt reassuring. It felt safe. It felt like an anchor during a very turbulent time in my mind.

It also felt so strange. So unlikely. To be a million miles away in a country so vastly different from Canada and find this arbitrary national treasure. I guess in a world of globalization this shouldn’t have been so shocking. But it still felt like a bit of a sign. Like the universe saying hello to me, making itself seen, reminding me that there is something bigger and greater out there.

A manifestation of that Living Hyphen come to life…by way of coffee.

Defining My Canadiana

About a month ago, I was invited to speak at a Filipina-Canadian roundtable with several Members of Parliament and the Minister of Women & Gender Equality. A group of 20+ Filipina-Canadian women was asked to come together and speak to the barriers and issues facing Filipina women, which the Minister would then bring back to Parliament.

My rallying cry has been around the importance of diversity, representation, and inclusion in the mainstream media and across all industries. And of course, I brought Living Hyphen with me to illustrate the work that I’ve been doing. My small but powerful contribution to make an impact in this space.

One of the Members of Parliament was eying the magazine I laid on the table, his interest piqued. He finally asked me to tell him more about it. I gave my usual elevator pitch, by now memorized by heart, “Living Hyphen is an emerging magazine that explores the experiences of hyphenated Canadians — that is, individuals who call Canada home but who have roots in different, often faraway places.”

I was not met with the usual spark of connection that I have grown accustomed to when explaining this passion project of mine to other people.

Instead, I was met with skepticism and a monologue.

“That’s interesting. You know, I used to just be a white man, but these days all these other labels are thrown around — I am a white, cis, straight, male, Protestant, Scottish/Irish, oppressor,” he said flippantly. “I don’t know if we’re headed in the right direction, to be honest. Why do we always have to think about identities these days? When do you stop being hyphenated and just become Canadian?”

I was instantly triggered by the mockery of his laundry list of identities, especially since he stands at the top of the privilege hierarchy across the major intersections of race, gender, and sexuality.

Immediately I was reminded of a conversation I had with the renowned Canadian playwright, actor, and poet Walter Borden who said, “There is a great contingent of people who say, ‘we can’t get anywhere until we get rid of our hyphens.’ But we can’t be Canadian until you understand my hyphen. What you’re asking me to do is to accept Canadiana on your terms. I am African-Indigenous. And that is my Canadiana.”

I wished so badly that Walter had been there to retort back to this MP as eloquently as he casually spoke those words to me.

Instead, I simply clapped back to tell him that as a woman of colour, I am not afforded the privilege to move through the world without thinking about my identity. Everywhere I go, the world around me reminds me of the colour of my skin, of the genitalia I possess.

The different parts of my identity all play into my calculation of how I move through this world. But I didn’t have the time to elaborate all the little ways in which this manifests — in the streets that I choose to take, in the way I automatically text my girlfriends “home!” after a night out, in the way people try to place me by asking where I’m from — innocently or not.

But if I’m being honest, his last question is one that I ask myself all the time. When do we simply become “Canadian”? How many generations does it take? What needs to change to make this happen? At what point do we drop our hyphens?

I know that naming this magazine Living Hyphen and openly embracing this hyphenated identity was a contentious decision, even/especially amongst those of us who are part of the diasporic community, who are of these hyphenated identities. I have received backlash from people of colour who have said that they do not need to qualify their Canadian-ness. That the hyphen, instead of acting as a bridge, represents a minus sign in their Canadian identity, rendering them less than their “Old Stock Canadians.”

It is a stance that I respect deeply, but one that I do not personally align with.

I will always be hyphenated. I will never be just Canadian. I am and will always be more than that.

I am and will always be Filipino-Canadian.

Pinay is another word for a Filipina

Without naming my roots, I would be doing an injustice to my ancestors and my heritage. I would, in a sense, be erasing it.

And so I will continue to press on and shout out my hyphenated identity everywhere and any time I can. Because to borrow Walter’s words: this is my Canadiana.

Unequal Pathways to Citizenship

But my conversation with this MP did not end there. He pressed on, “Why can’t we just be happy that we live in Canada. When people move to Canada, they have a path to citizenship that so many in the world envy.”

I took a deep breath, looked to my sisters around the table for solidarity, and mustered up all the courage inside of me to challenge this man in power.

“With all due respect, our paths to citizenship are not equal. You cannot come into a Filipina-Canadian roundtable and say such a thing about paths to citizenship. Are you not aware of the ways in which the majority of our people have come to this country?”

I was furious that this man, this politician, had both the ignorance and audacity to come into this space without even understanding our community’s history and present-day circumstances.

“Do you not know about the Live-In Caregiver program and how it has separated our peoples’ families for years, sometimes decades? Sometimes only to deny these women citizenship after years of servitude?”

If you, dear reader, don’t know about the history of migration trends for the large majority of Filipino-Canadians through the Live-In Caregiver Program, I encourage you — implore you, really — to read this powerful snapshot from the Globe & Mail as a primer.

But in that moment, I wasn’t only talking about Filipino-Canadians. I was also talking about so many other people from various nationalities who face immense barriers navigating our immigration system.

I was also talking about the inhumane immigration detention system that locks up unwanted immigrants indefinitely across the country, many in maximum-security jails, despite having no criminal record.

I was also talking about how the first settlers of this country stole the very land that we are on and how the state continues to treat Indigenous peoples as second-class citizens at best and as sub-humans at worst.

That we live in a country where men like him hold power makes me afraid, ashamed, discouraged, and outright furious.

How can this be the True, North, Strong and Free?

Interrogating Ourselves and Embracing the Contradictions

But I love Canada. And I am proud to be Canadian. I am deeply proud that my family laid its roots in Scarborough, settled in Markham, and that I am now living my adult life in the heart of Toronto — all widely and vastly diverse cities that has informed so much of my ideas and beliefs around the importance of diversity, representation, and inclusion. And I am unbelievably grateful to live in this country that has afforded me and my family opportunities that my ancestors only dreamt of.

But as I dig deeper into my identity, my ancestry, my roots, my adopted homeland, and this complicated world we live in, I am also becoming much more critical and yes, “woke”, than I have ever been.

I am coming to grips with my role and responsibility as an immigrant settler on Turtle Island — as someone who has benefitted and continues to benefit from colonial violence on this land.

I am coming to grips with my own privilege as a middle-class Filipina-Canadian whose parents entered this country through the Skilled Worker program with familial support already in place here for years — and who therefore had numerous advantages ahead of so many newcomers in this country (an apartment, a steady household income, a solid support system — just to name a few.)

I am coming to grips with how this country has been good to me and my family, but has not been so good to so many others in my own community, and to all other marginalized communities.

I am coming to grips with the systems of oppression, the inequality, the inequity, and the injustice that permeate so many levels and spaces of this country.

Canada Day used to be a simple, easy, fun day off where I would watch some fireworks, wave around a flag, and have a drink.

I’m still doing that today. But I’m also reflecting deeply on what it means to be a proud Canadian, writing this blog, and thinking up ways to push Living Hyphen forward to capture all these complexities.

Is it possible to do it all? I personally think so.

I always say that the problem with our society today is that we have such a low tolerance and capacity for complexity, for nuance. We want simple. We hold fast to binaries and absolutes. We find it so difficult, so impossible to hold two truths at once.

As immigrants, we content ourselves by saying, “well, life is better in Canada than it is in the Philippines (or wherever you might be “from”). Look at how much better our lives are.”

But better does not mean good enough. Better does not even mean better for all, only better for some.

And so we must press on. We must continue to interrogate the systems around us, interrogate ourselves and our very own beliefs. We must think critically. And we must speak out and stand in solidarity with other marginalized communities, not just our own. Not just when it is convenient.

And I think we can do that while still harbouring a love for this country.

We can and should do that precisely because we love this country.

With so many questions swirling in my head after my trip to the Philippines, I wrote that my relationship with my ancestral home is like this shape-shifting thing that I just can’t grasp. And every time I feel like I’m closer to understanding this place, something within me, within the country, and/or between us changes, and I am left puzzled once again.

I didn’t realize then that the same is actually true for my relationship to Canada, my adopted home.

And so this blog remains a work-in-progress — a piece to be revisited, revised, and possibly rewritten many times over.