Living Hyphen is a community that explores what it means to live in between cultures as what we’ve been calling “hyphenated Canadians” — that is, anyone who calls Canada home but who may have roots elsewhere.

But what does it even really mean to be Canadian?

Growing up, I had the iconic Molson beer commercials to define that for me.

As “Joe” would have it: “I have a Prime Minister, not a President. I speak English and French, NOT American. and I pronounce it ‘about’, not ‘a boot’. I can proudly sew my country’s flag on my backpack. I believe in peacekeeping, not policing. Diversity, not assimilation. And that the beaver is a truly proud and noble animal…Canada is the second-largest landmass, the first nation of hockey, and the best part of North America!”

Fast forward some decades later, we now have Asian-Canadian actor Simu Liu rewriting that script for his contemporaries. In his version, he proudly proclaims, “I proudly fill my days with Canadian inventions like basketball, Timbiebs, or insulin…whether you call it a cabin, a camp, or a cottage — we spell Weeknd without the third “E”. I speak English and Mandarin et une petite peu Francais. I grew up on ketchup chips, roti, and Jamaican beef patties! Canada is a place where the government is also our drug dealer and we’re into snowboarding — not waterboarding!––and where a woman always has the right to choose.”

Now, of course, I know these statements were made to be snappy and flashy for the purposes of virality, and that they can’t possibly capture all the complexities of what we really mean when we talk about being Canadian. But it is, in my view, very telling of the mainstream’s shallow conception of what it means to be Canadian.

This Canada Day, I want to take a moment to reflect on this question of what it means to be Canadian much more deeply. I challenge you to do the same.

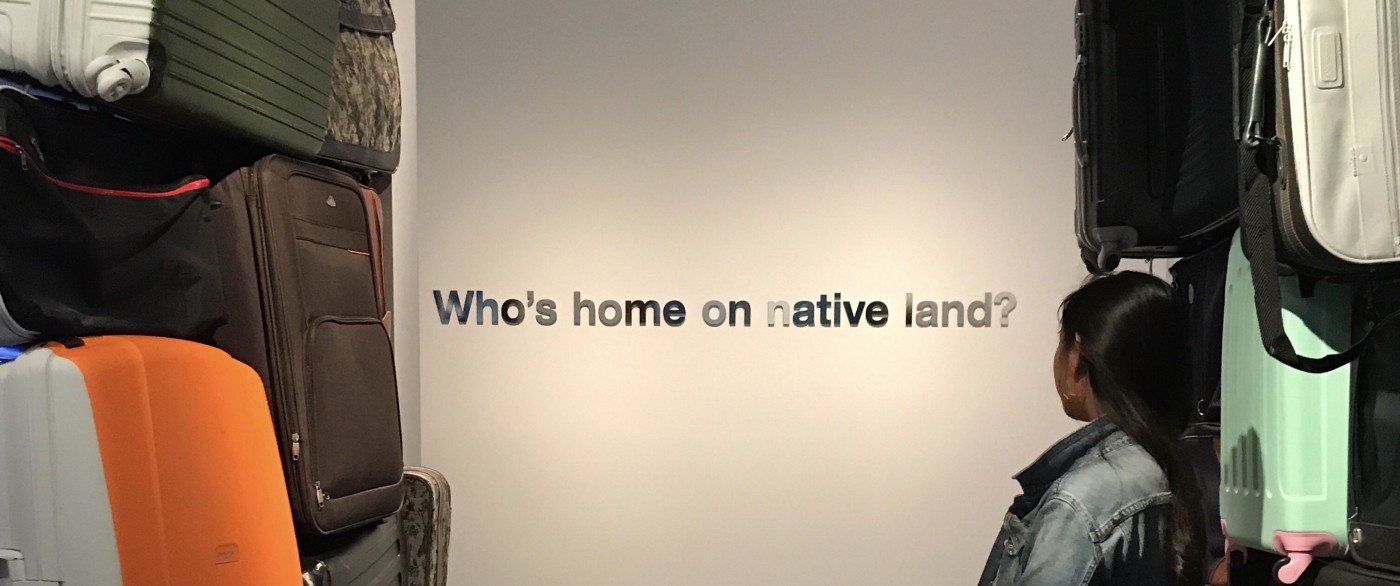

Reckoning with Our Role & Responsibility As Immigrant Settlers

What we now know as “Canada” is a nation of immigrants who have come to settle on Indigenous land. Regardless of when we or our parents or our grandparents — or however far back migration may go in our lineage––we are settlers on Turtle Island.

There once was a Canada Day not so long ago when I was grappling to hold my love of country alongside my personal reckoning as an immigrant settler. Can I love Canada, a country that has given my family so much after leaving a country that has given so little (for historical and political complexities I didn’t understand then), while also holding it accountable to its sins of genocide and continued colonization? I thought it was possible once but I’ve been finding it harder and harder to do that over the last few years.

However uncomfortable it may feel, part of being Canadian to me now means being someone who has benefitted and continues to benefit from colonial violence. It has been 155 years since the “birth” of this nation and the process of colonization is still alive and well today, continuing to inflict violence on Indigenous lands, cultures, and bodies.

Don’t know what I’m talking about? Just take a moment to learn more about the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls, the lack of clean drinking water in Indigenous communities, the construction of pipelines on unceded territory, and the treaties across the country that continue to be broken everyday – as only a start.

Being Canadian means having to continuously learn and unlearn our role and responsibility in the genocide, displacement, and theft of land from Indigenous peoples, as well as dismantling the mentality of white supremacy that exists as a result of this colonization and that continues to also oppress Black and communities of colour.

While land acknowledgments have become more fashionable in recent years, we must go beyond the performance of these words and move towards action. More specifically, towards the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action.

While Living Hyphen is a community that includes Indigenous peoples from many nations, I would be remiss not to acknowledge that our community is predominantly made up of immigrant settlers, people from diasporas from all around the world.

As such, we’ve created a dedicated hub full of resources on Indigenous Allyship to work in solidarity with the struggles of Indigenous nations for sovereignty, land, and freedom. I urge you to go through this resource and continue your own journey to (un)learn your role and responsibilities as an immigrant settler.

Artwork by @chiefladybird and @auralist.

Pride and Gratitude Not for Canada, but for My Ancestors

In 2019, I wrote an essay called, “Reflections on Being Canadian: A Rough Draft, Probably A Lifelong Work-In-Progress”. I wrote about my conflicted feelings of national pride vs. my growing knowledge of the racism, the injustice, and the inequities that are the realities of this country. I wrote:

But I love Canada. And I am proud to be Canadian. I am deeply proud that my family laid its roots in Scarborough, settled in Markham, and that I am now living my adult life in the heart of Toronto — all widely and vastly diverse cities that has informed so much of my ideas and beliefs around the importance of diversity, representation, and inclusion. And I am unbelievably grateful to live in this country that has afforded me and my family opportunities that my ancestors only dreamt of.

Canada has been good to my family. I can’t deny that. But I also know this is only because we have been deemed skilled and educated enough by this colonial government. My parents moved here through the points system in the early 90s. Both Ma and Pa held Master’s degrees, spoke fluent English, and worked in the highly sought-after IT field. We were, therefore, “worthy” and “good” immigrants that were “let in” to the country.

Not all immigrants can say the same. Not all immigrants have been treated as kindly.

After years of ongoing learning and unlearning, I no longer hold that kind of love or pride that 2019 Justine felt for this country. After the shameful “Freedom Convoy” proudly waved the Canadian flag while shouting messages of white supremacy during a global pandemic, and as I continue to learn more about and bear witness to the deeply unjust and inequitable policies that our government wields against some of the most vulnerable and marginalized in our society, I now feel a deep revulsion to any kind of nationalism. I refuse to hold any kind of gratitude to a colonial state that prioritizes some needs over others and only according to how much they adhere to colonial standards of “excellence”. After all, our acceptance will always be conditional.

And so do I really owe a debt of gratitude to this country and its government? Do I thank them for deeming my family good enough?

What I am realizing now is that this gratitude and love I’ve felt for this country has been misdirected towards an institution, instead of the very people who made my existence and all the comforts I now enjoy possible.

This Canada Day I give thanks to my parents and family who did what we and our ancestors always do best — find opportunities to survive and thrive. It is they who carved the path for our family’s future, for our health, and our prosperity today.

The matriarchs of my family survived and resisted a brutal dictatorship in our home country of the Philippines and moved to a place where they knew their children and grandchildren would have better opportunities. They crossed oceans, endured prolonged separation from their loved ones, and made a gamble to move to a foreign land they knew nothing about so that we would not just survive, but so that we would thrive.

No nation did that for us. The women in my family did that for us.

Me and the matriarchs of our family.

Listening to and Amplifying the Voices of Newcomer Canadians

When I think about my Ma and my Titas who moved around the world in search of better opportunities —from the Middle East to across Southeast Asia, from Europe then to Canada — I think about the many newcomers who do this for their own families today. The many newcomers who cross oceans every day in search of the promise of something better for themselves, and for their children, and their descendants.

According to the 2016 census, more than 7.5 million people, or 21.9% of the Canadian population reported being landed immigrants or a permanent residents. Moreover, 1 in 5 Canadians is foreign-born. Newcomers are vital to the social fabric of Canada.

And yet, their voices and their stories are all too often ignored or erased from mainstream narratives, from our definitions of what it means to be Canadian.

That’s why I am so excited that Living Hyphen has partnered with The Department of Imaginary Affairs (DIA) — a national nonprofit organization focused on understanding the evolving definition of what it means to be Canadian from new and developing Canadians.

Together, we are bringing you a special collection called The Stories of Us, the first-ever English as a Second Language collection of stories written and told by newcomers, for newcomers.

The stories that I have had the privilege of curating for this magazine have shown me a whole new dimension and depth to this hyphenated experience that I don’t think I myself fully ever experienced.

I moved to Canada from the Philippines when I was just four years old and while I was once a newcomer myself, I was too young to understand what that meant. My parents shielded me from a lot of the struggles, and my memory doesn’t hold the excitement or curiosity of moving to a new and unfamiliar place anymore.

The Stories of Us has given me a glimpse into the gamut of emotions and experiences my parents could have, may have, probably, definitely experienced. And to know that this is the experience of so many other new Canadians has been incredibly eye-opening to me.

The people and stories I have encountered while working on this magazine have changed me. They have shown me, on a whole other level, just how nuanced and complex each and every one of our journeys to and on this land can be. They have shown me how we are all constantly unfolding.

This Canada Day, I invite you to be opened and changed by these stories too. Pre-order your copy of The Stories of Us today.

An Evolving Definition

What it means to be Canadian is an ever-evolving and ever-changing definition for me. It will likely be a life-long relationship I attempt to understand and untangle. And so I’ll wrap up as I did many moons ago:

Every time I feel like I’m closer to understanding this place, something within me, within the country, and/or between us changes, and I am left to learn all over again.

And so this blog remains a work-in-progress — a piece to be revisited, revised, and possibly rewritten many times over.

A few years ago, I wrote an essay called, “Reflections on Being Canadian: A Rough Draft, Probably A Lifelong Work-In-Progress”. It was an attempt to unpack and take stock of the many complicated feelings I have about my identity as a Filipina-Canadian. As in much of my work, I reserved the right to revisit, revise, and possibly rewrite that piece many times over as I learned more about myself, my adopted homeland, and everything that lies between and beyond. Instead of deleting or revising that post directly, I’m adding this as a kind of addendum. I think it’s important to preserve our growth and journeys as human beings who are constantly learning and (un)learning their ideas of themselves and of the world.